The Mitford Industrial Complex

A few weeks ago my friend Heather and I decided to read Jessica Mitford’s memoir Hons and Rebels together. A mini bookclub, and an excuse to socialize. I had thought I’d read Hons and Rebels years ago, but it soon became apparent to me that I had gotten through only half of it before tapping out right before the Spanish Civil War.

Jessica Mitford was one of six sisters in the storied Mitford family. Their father was in the House of Lords but they lived in that odd, rural way some English aristocrats seem to live, raising chickens, with leaks and draughts all over the house, but endless servants, horses, and dogs. They had six daughters and didn’t believe in educating them, so all six of them stayed at home, soaked in eccentricity, with little social life until they ‘came out’ in society at seventeen or so. Nancy, the eldest, became a novelist and a member of the Bright Young Things set in the 1920s – her novels (excellent sick-bed reading) I read about a decade ago, and she was my introduction to the Mitfords. Pamela spent her childhood wanting to be a horse, and ended up having a pleasant life on a horse farm with an Italian horsewoman, her ‘companion’ of over 40 years. Diana was a Bright Young Thing too. Then she got divorced, became a fascist, and married Oswald Mosely, leader of the British Union of Fascists. Unity was the more rabid fascist, so devout that she was carving swastikas into the windows of the family estate as an adolescent, taking off to Germany as a teenager to find Hitler and his friends at a beer hall and stare at them intensely until invited for supper. She became Hitler’s close confidant – he described her as a perfect example of Aryan womanhood – and she attempted suicide when Britain declared war on Germany. The childhood ambition of Debbo, the youngest, was to marry a Duke, and she did, taking charge of his ancestral home, Chatsworth House. Jessica was the communist, the second-youngest. She ran away at nineteen – she eloped with her second cousin to go fight in the Spanish Civil War. They never quite made it to the war, but they caused a scandal, with future Prime Minister Anthony Eden intervening to try and get them back to England. The couple moved to London’s East End, and then to America shortly before WWII broke out. Her husband was killed in the war, which is where Hons and Rebels ends, but Jessica went on to become an excellent investigative journalist – I bought a beautiful used copy of The American Way of Death about five years ago in Los Angeles, and it is wonderful.

When you start reading about the Mitfords what you get are a lot of this: “Oh no! Not another book about the Mitfords!” (That one is courtesy Tina Brown in the New York Times five years ago). Heather and I consulted about this, because there certainly seems to be a sentiment among women older than us that the Mitfords are a Thing, the subject of a Mitford Industry spawning many books and curios. You encounter a lot of articles and op-eds written by women in their forties and fifties who’ve come out the other side of a Mitford obsession, and other articles suspicious of a romantic interest in members of the English upper classes (the implication being, I suppose, that interest equals Toryism, the same unease some people have about fans of The Crown (I like The Crown, for what it’s worth)). But Heather and I are in our thirties, and suspect the whole Mitford thing rather passed us by. They feel very niche (although we are neither of us English, for the record, and maybe that has something to do with it?). I know from working at the bookstore that Hons and Rebels was lucky to sell one copy a year, Nancy Mitford’s novels sold occasionally, about as often as other Bright Young Things (Anthony Powell, Sylvia Townsend Warner, the lesser-known Evelyn Waugh novels). There were two or three biographies and volumes of letters, but they mostly sat there getting shelf-worn, with only me coming along to paw at them occasionally, paging through when I was meant to be shelving, and ultimately putting them back (books on the Mitfords tend to be brick-sized).

At any rate, it was weirdly fascinating to read Hons and Rebels at this particular moment, when families and friendship groups are politically polarized, communists and fascists firmly back in the political game (I was reminded a great deal, while reading, of a time when I, a baby socialist, stormed out of a family lunch mid-meal when my grandfather called Oswald Mosely “a great man.”) The first third of Hons and Rebels has the cosy Englishness of the early twentieth century (it makes a lot of sense that it’s J.K. Rowling’s favourite book). It’s the same thing you find in books like Brideshead Revisited or I Capture the Castle, Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals, Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time, and yes, Nancy Mitford’s novels. The family is made familiar and comical through ingenious tricks of characterisation that are very similar to Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon. It is very rare that I actually laugh while reading a book and I laughed every second page of Hons and Rebels (V was referring to it as “your Mitford giggle”). Jessica Mitford’s political awakening is a big part of the memoir, but she’s also very honest about the ways youthful political awakening can be more invested in the symbols and passion than the nitty-gritty of the ideology. There’s a very amusing section when she describes sharing a bedroom with Unity: they divided the room down the middle. Unity decorated her side with pictures of Mussolini, Hitler, and Mosely, swastikas, record collections of Italian and Nazi youth songs. On Jessica’s side was a small bust of Lenin, copies of the Daily Worker, and a Communist library (which was a bit muddled – Lenin and Stalin, yes, but also writers who she’d heard her parents describe as ‘Bolshevik’ - Bertrand Russell, Bernard Shaw, and Lytton Strachey). “Sometimes,” she says, “we would barricade with chairs and stage pitched battles, throwing books and records until Nanny came to tell us to stop the noise.”

The book swerves away from cosy when she flees to fight in the Spanish Civil War. There are semi-tedious sections on Esmond Romilly, the cousin she married, who comes across as a pompous and arrogant clever clogs, her devoted descriptions cannily letting you know the marriage probably wouldn’t have been a happy one if he’d lived well into adulthood. It becomes positively dull once they move to New York in the 1940s, and there is an incident in London when they’re living in Poplar when her five-month old daughter contracts measles and dies (this occurs in the same neighbourhood as Call The Midwife, the greatest television show on working women ever made, and, Heather rightly pointed out, a four-season advertisement for Britain’s NHS). That tragedy is rather skipped, hopped, and jumped over, the implication being that there is no time for any sentimentality in the English upper classes, Communist or otherwise.

For all that, the book is ever so slightly evasive – a lot of wit, no vulnerability. Part of the reason it falls down at the end is due to the subtlety with which Mitford wrote – her style wouldn’t allow for political analysis of her family, or her position in society, or what came afterward. When your approach is arch and winking – all show and no tell – you can inadvertently de-politicise your writing (I like this conversation between Viet Thanh Nguyen and Charles Baxter a lot, on this idea). We never really come back to the genuinely horrific things committed by Diana and Unity, or any of her family, once they’ve emigrated to America. But there is a touching part quite near the end where she returns to Unity – the war was beginning, and news of Unity’s suicide attempt reached Jessica in Washington. She admits that, regardless of Unity’s political affiliations, she was always her favourite sister. She recalls “my huge, bright adversary of the DFD…when we used to fight under banners of swastika and hammer and sickle.” There is an honesty I admire in that, the honesty of politics when you’re young, when it can all seem still an extension of childhood games. It’s all fun and games and cosy family anecdote until a war breaks out, until people start getting killed.

Also, apologies, I did not write this newsletter for the last two weeks – I was having a hard time, and while I like writing about what I’m reading, it is a lot of work, for not much yield (there is a paid subscriber option, by the by). At any rate, I’m still figuring out how best to go about this.

Books mentioned:

Hons and Rebels - Jessica Mitford (US, UK, AU)

The American Way of Death - Jessica Mitford (US, UK, AU)

The Pursuit of Love - Nancy Mitford (US, UK, AU)

The Six: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters - Laura Thompson (US, UK, AU)

The Sisters - Mary S. Lovell (US, UK, AU)

The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosely (US, UK, AU)

Dance to the Music of Time - Anthony Powell (US, UK, AU)

Lolly Willowes - Sylvia Townsend Warner (US, UK, AU)

Vile Bodies - Evelyn Waugh (US, UK, AU)

Brideshead Revisited - Evelyn Waugh (US, UK, AU)

I Capture the Castle - Dodie Smith (US, UK, AU)

My Family and Other Animals - Gerald Durrell (US, UK, AU)

Family Lexicon - Natalia Ginzburg (US, UK, AU)

What I’ve been reading lately:

Hons and Rebels - Jessica Mitford (US, UK, AU)

The Life of the Mind – Christine Smallwood (US, UK, AU)

Half In Love – Maile Meloy (US, UK, AU)

Wittgenstein’s Mistress – David Markson (US, UK, AU)

Go Tell It On The Mountain – James Baldwin (US, UK, AU)

Gay Bar – Jeremy Atherton Lin (US, UK, AU)

Ninth Street Women – Mary Gabriel (US, UK, AU)

What I’m looking forward to:

Three Rooms – Jo Hamya (US, UK)

The Art of Losing – Alice Zeniter (US, UK, AU)

Personhood – Thalia Field (US, UK, AU)

Something to look at:

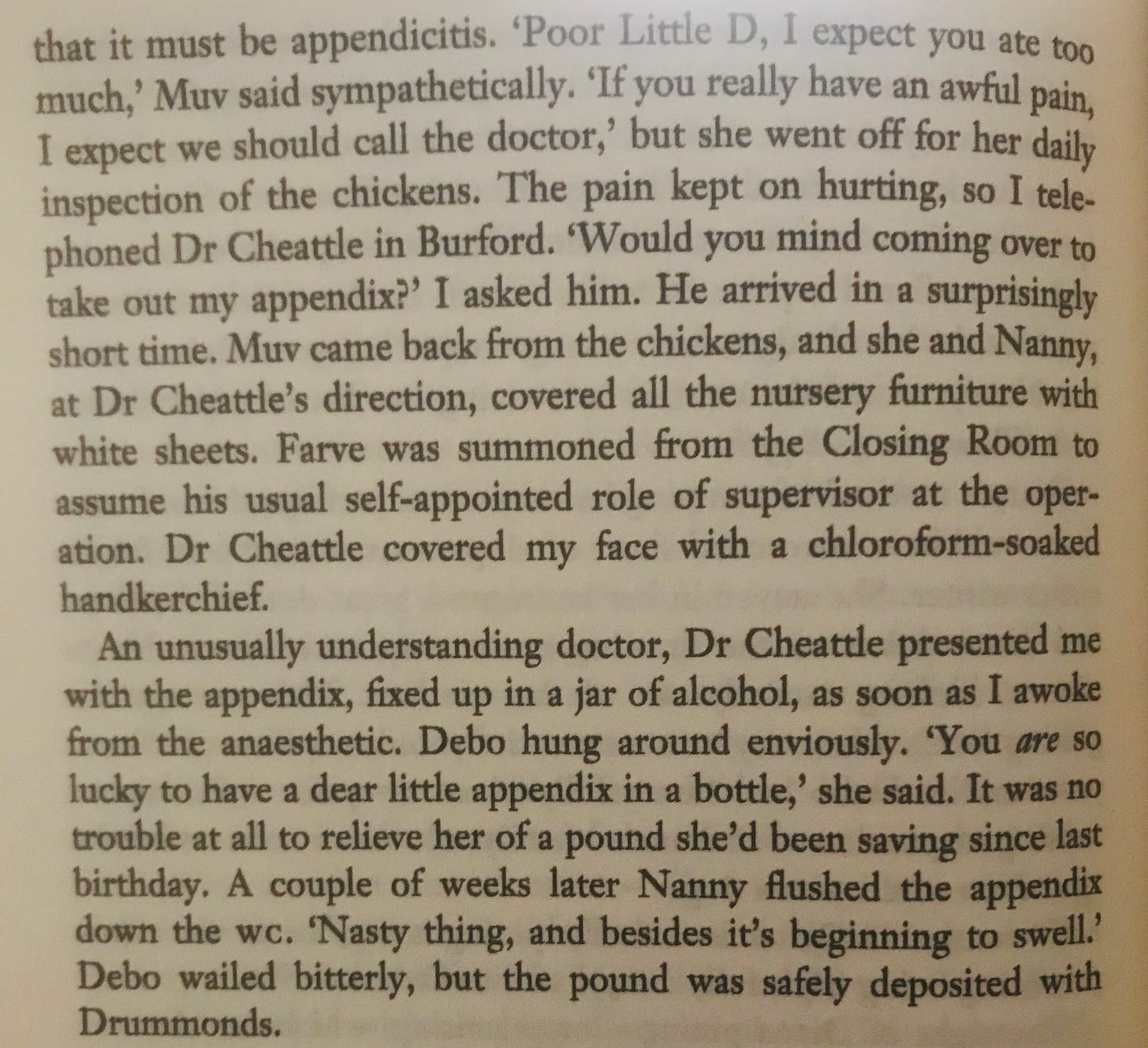

— from Hons and Rebels by Jessica Mitford

Some notes:

I was included in a very lovely round-table discussion Lithub held with writers who address climate change, alongside Kim Stanley Robinson, Lydia Millett, Omar El Akkad, John Lanchester, Diane Wilson, and Pitchaya Sudbanthad. Also, my novel was also shortlisted for the UTS Glenda Adams Award for New Writing as part of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards.