On the flaneuse, and women walking in the city.

When I was in university I did a lot of walking. I still like walking – my boyfriend and I walked for six hours on Saturday – but nothing had quite the same fervour and intensity as the walks I made clean across Sydney when I was nineteen and twenty. As a consequence, I did a lot of thinking about walking as well.

The first high distinction I got at university was for an essay I wrote about Baudelaire. I was taking a class on literature of the streets, and in that essay I wrote about the idea of the flaneur, the walker in the city streets. The figure of the flâneur (who was less historical reality than a kind of useful idea) was made possible by the construction of Haussmann’s boulevards in Paris, which widened the streets so that the French state could more easily crush insurrection. The wide streets had the effect of making the street a place a public spectacle. It was around this time in the nineteenth century that urban life became thought of (and experienced!) as fragmented and alienating, but also liberating in its anonymity. And instead of speaking with those around you, you looked. In Baudelaire’s poem ‘To A Passerby,’ the poet can only glimpse the desired woman passing him in the street, for instance, meeting her glance before she disappears into the crowd that swallows her up. Baudelaire himself is often thought of as the archetypal flâneur (Walter Benjamin described him as somebody who “loved solitude, but (who) wanted it in a crowd.”) Baudelaire’s flâneur was a distinctly separate entity to the crowd: in it, but never of it. (This is all important, I promise).

During the late 1980’s a debate took place amongst feminist scholars (Janet Wolff, Susan Buck-Morss, Elizabeth Wilson), about whether a female flâneur, or ‘flâneuse’ was possible. Why couldn’t a flaneuse exist? Because she was never anonymous. She could never pass through the crowd unnoticed. (Lauren Elkin’s book Flaneuse is excellent, and a modern-day exploration of the idea, I highly recommend it). The definitive act of the flâneur was walking for pleasure. Rebecca Solnit, who devoted an entire book to the subject of walking, was of the opinion that there are three conditions for taking a leisurely walk: “free time, a place to go, and a body unhindered by illness or social restraints.” The fact is that women’s bodies and their sexuality have nearly always been a public concern rather than a private one, and so they are often subject to the restraints that you need to be liberated from to walk freely. Respectable women didn’t walk alone.

But, nineteen-year-old me asked, what’s the big risk in being seen as unrespectable? Walking around alone held an element of danger, sure - I could be followed or attacked - but it was statistically unlikely, and whether people looked at me or not was not my concern.

The professor who taught that class in which I wrote about Baudelaire eventually became my thesis supervisor. She was the first person to hand me a Rebecca Solnit book, the book on walking, as research. Reading Solnit was an enormous step for me. She is an excellent writer of the American West, of nature, of deserts, and I learned from her how to write something structured intuitively instead of linearly, mimicking the movement of thought (or, my thoughts, which do not progress in an orderly fashion, but dart all over the place before returning to a kind of central point). For years I would say Solnit was one of my favourite writers, but I haven’t said that in some time. At a certain point, her writing began to feel to me as though it had lost its intellectual rigour. I disagreed with some of her arguments, and when people came into the bookstore I had perfected my ‘read Rebecca Solnit with caveats’ spiel. Everything before she got on Facebook, I said, is good. I have read and re-read Savage Dreams, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, River of Shadows, and Storming the Gates of Paradise. But I haven’t been able to bring myself to read the recent books. Anyway, my point – and it’s taken me a while to get to it, I admit - is that I bought her newest book with much trepidation.

Recollections of My Non-Existence is, mostly, about Solnit’s coming of age as a woman and a writer in San Francisco in the early 1980s. At the same time, I was reading Lisa Robertson’s The Baudelaire Fractal, which is a novel about Robertson (or a Robertson-like narrator) coming-of-age as a woman and a writer in Paris in the early 1980s. Reader, these women are exactly the same age – Solnit was born in June 1961, Robertson in July. They have been influenced by and reference many of the same books and texts. They have both written books about women walking alone in the city. And the experience of reading them both at the same time is one I cannot recommend enough, because they offer radically different reflections on a female experience of urban life, a becoming-through-the-city which seems to have hit them, and me, with a particularly intense force at the age of twenty.

When I was writing my thesis I became obsessed with the idea of writing as a kind of articulation – inscribing oneself into space, becoming through movement. I don’t know how well those ideas stand up now, but they were very urgent to me when I was young. Robertson’s book – dense, ludic, an exceptional poet’s novel – is deeply involved with that concept of language. In fact, the premise of the book is that one day the narrator wakes up and understands that she has written the works of Charles Baudelaire. It sounds like a whimsical possibly-magical-realist conceit, but she spends much of the book explaining that she really has, to the point that when I finished it in bed this morning it suddenly clicked. She really had written the complete works of Baudelaire! Everything for Robertson is a form of becoming. Her experience of poverty, sex, desire, bad jobs, writing, language itself, it is all an exercise in form, in the fluidity and mutability of enunciation. She captures the excitement and liberation I felt in the city at the same age, a sense of agency.

Flitting back and forth between Solnit and Robertson was necessary because reading the Solnit made me angry, as I had expected it might. Not all of it, I should say. The sections in which she writes about the desert, and landscape, San Francisco itself – those were beautiful, and what I wanted from her, and the longing to read her write about them again was what compelled me to buy the book in the first place. But my marginalia in the section titled ‘Life During Wartime’ becomes increasingly irate in tone. It starts at ‘ugh’ and ‘good grief’ and ‘oh for fuck’s sake’ and ends in long ripostes that take up the margin of the whole page. ‘Wartime’ is patriarchy, to Solnit. ‘War’ is what she endured walking around the streets of San Francisco in the 1980s. Cat-calls, street harassment, once being followed home. Women – white women – are always at risk of being murdered and raped, at all times, in this view, and those who do not believe so, those who don’t experience the world this way, who disagree with Solnit (like me), are afflicted with false consciousness, poor things. She conjures a landscape of fear without nuance, and in so doing she does the worst thing – she reinscribes the narrative of white women’s fear. When we tell the story of a young, white woman imperilled on the street, we erase the reality – that women are more likely to be killed in their homes by men they know (husbands, fathers), and that women of colour experience violence at much higher rates than white women. If white women are imperilled and vulnerable (albeit angry) as Solnit makes them out to be, then they are implicitly construed as the real victims of patriarchy. This narrative conceals the fact that white women are often complicit in systemic violence against women of colour and poor women, and the beneficiaries of that violence. The mythology of endangered white women, terrified in San Francisco as she walks down the street, is the same mythology central to white supremacist ideologies the world over. White women teach one another that being afraid will keep us safe, and we absorb it as a lesson, we convince ourselves that we live in a warzone, that we must be vigilant, and afraid, even if we’re angry about being afraid. It is cast as a form of rational thinking and responsibility. It isn’t.

There is nothing like ‘Wartime’ in Robertson’s book. There is playfulness, intellectual rigour, the pleasure of gender fluidity, of nice jackets, of sex with men whose names she can’t remember, of a poet ‘becoming’ in the streets of a city. It is a more recognisable experience to me, more ‘relatable’ as it were. These women, who have read the same books, who were born only a month apart, have such different takes on that period of their lives. But it is Roberton’s that I prefer. Roberton is ‘the Baudelairean girl’ – “The girl within the Baudelairean body of work will undo it by repeating it within herself, as indeed she repeats girlhood, misshapen. She’s always and only untimely, apparitional, forbidden, monstrous, a stain on authority…The Baudelairean girl repeats her monstrosity for the benefit of a time to come. She will break open beauty and she will break open literature.”

Books mentioned:

Selected Poems – Charles Baudelaire (US, UK, AU)

The Writer of Modern Life – Walter Benjamin (US, UK, AU)

Flaneuse – Lauren Elkin (US, UK, AU)

Wanderlust – Rebecca Solnit (US, UK, AU)

Savage Dreams - Rebecca Solnit (US, UK)

A Field Guide to Getting Lost - Rebecca Solnit (US, UK, AU)

River of Shadows - Rebecca Solnit (US, UK, AU)

Storming the Gates of Paradise - Rebecca Solnit (US, UK)

Recollections of My Non-Existence – Rebecca Solnit (US, UK, AU)

The Baudelaire Fractal – Lisa Robertson (US, UK, AU)

What I’ve been reading lately:

Burnt Sugar – Avni Doshi (US, UK, AU)

Ninth Street Women – Mary Gabriel (US, UK, AU)

Anniversaries 1 – Uwe Johnson (US, UK, AU)

Vanishing New York – Jeremiah Moss (US, UK)

What I’m looking forward to:

Everything New – Rosecrans Baldwin (US)

Seek You – Kristen Radtke (US, UK)

Everybody Knows Your Mother Is A Witch – Rivka Galchen (US, UK)

Something to look at:

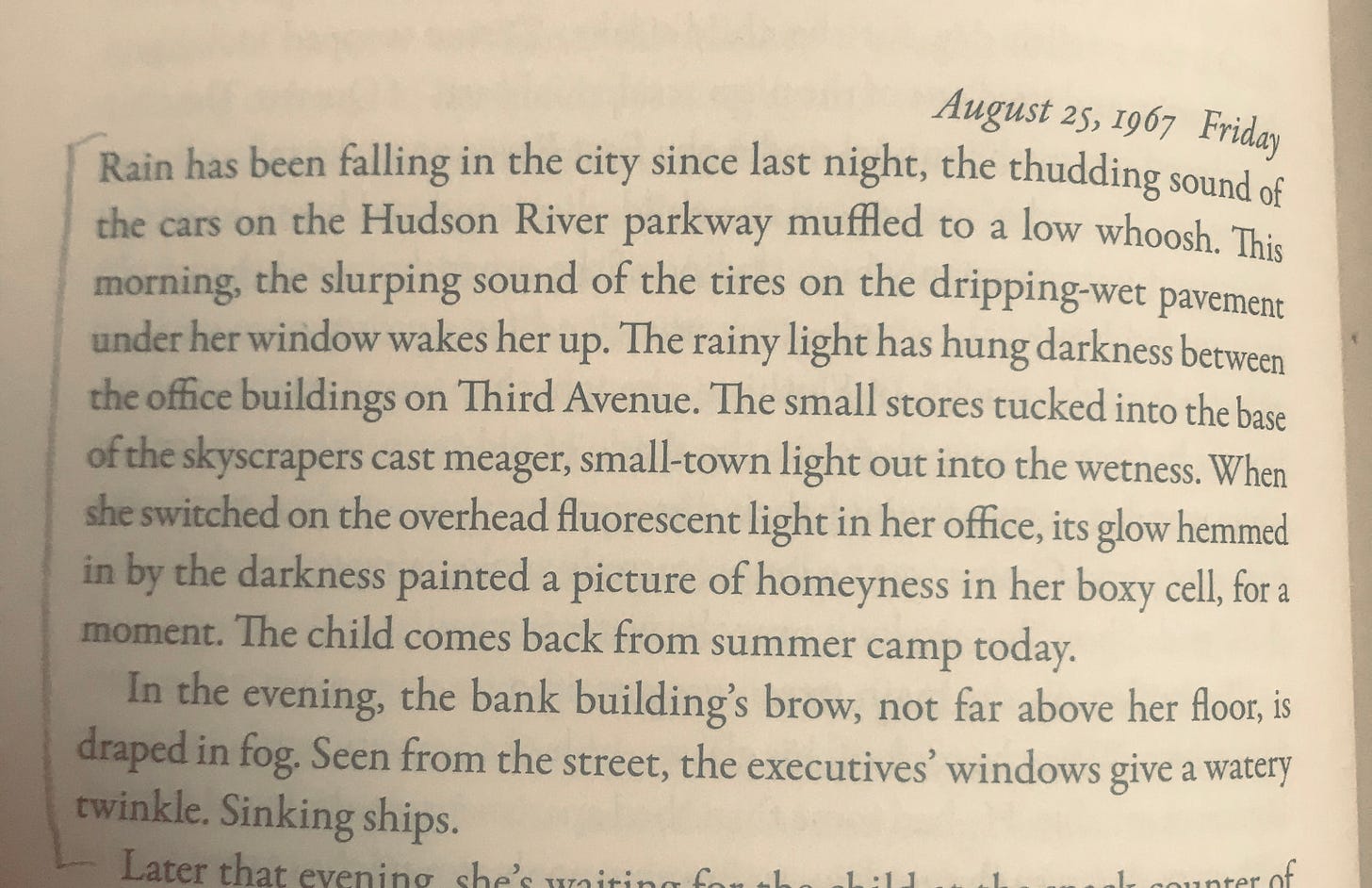

— from Anniversaries 1, by Uwe Johnson

Some notes:

My book came out in America last week. It’s sold out on Bookshop.org but independent bookshops have lots, and it’s easy as pie to order it online directly from them. I did a lovely interview with Jeannie Vanasco for The Believer, and another with Gauraa Shekhar for Maudlin House. I wrote an essay about climate change fear and love of nature and my intense relationship to my house plants for Literary Hub. I did an interview for Shelf Awareness about my reading habits where I sound like an absolute lunatic. Also, I am doing some more events - the next one will be with Amina Cain on January 25 with Skylight Books in Los Angeles. Virtually, of course.