Helen Garner and the In-between Space

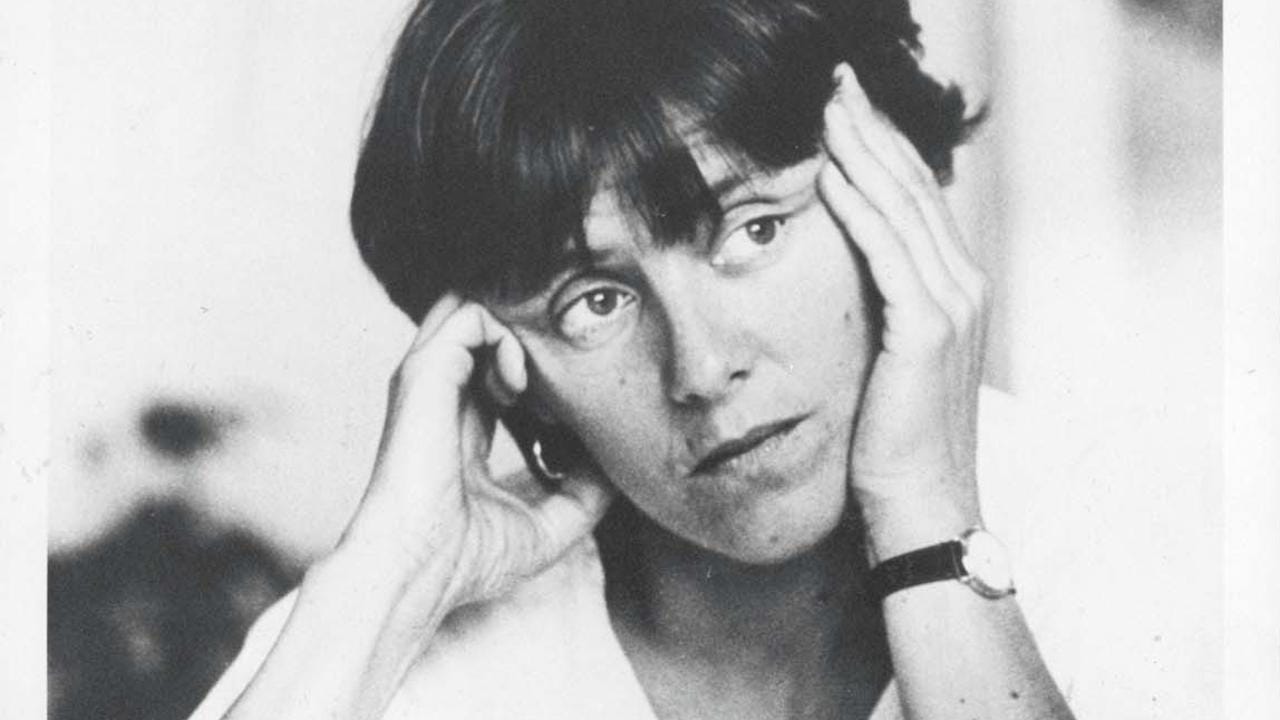

For the last five days, I’ve been in Perth, attending a symposium at the University of Western Australia on the work of Helen Garner. A five day trip from Berlin to Australia - my mother warned me it was madness, and she was right. Doubly mad when pregnant (the compression tights, for starters). But as soon as I was invited I was certain that I’d attend, no matter the 22 hour flight. When else do you get to deliver a paper on one of your literary forebears, when they’re present in the room?

I’m on my way back to Berlin now, with a suitcase stuffed full of Arnott’s biscuits, paw paw ointment, and red gum honey, and I thought I might as well post what I read yesterday. It was a terrifying paper to deliver, but I meant, and mean, every word. Imagine, while reading, a woman entirely unable to make eye contact with anybody in the room, clutching a glass of water she’s not drinking from, and the subject of the paper sitting in the corner.

Note: parts of this paper rework an essay I published in Lithub five years ago, and there are some similarities.

On Helen Garner

During the year I that was twenty-two I often went to a bar on Glebe Point Road where flying foxes ate figs in the Moreton Bay, and I drank whatever was cheapest, and I read anything I could find written by Helen Garner. The bar belonged to a used bookstore, with a very good but much neglected section for Australian literature. I successively bought, and sometimes shoplifted, every used copy of Garner’s books from the shelf in the back room, taking them with me out to the courtyard and the figs and the bats with my cheap wine.

Out there, one evening, opening a collection of essays called The Feel of Steel, I read this:

“What if somebody’s heart has been broken one time too many? What if this person has become stupid with sadness? If she can’t sit still or concentrate for more than twenty seconds at a stretch? If the part of her mind that used to grasp structure and form has suddenly lost its grip? What if the whole world of literature looks like a burnt-out landscape? What use to such a person is the mighty cataract of books that’s forever crashing down, blotting out the sunlight and choking the universe? Is there anything she can salvage from what she’s read in the past that will be of any use to her whatsoever?”

This is the opening to the essay ‘Woman in a Green Mantle,’ and I underlined every word of the paragraph.

At the time I too was stupid with sadness, and I was finding that the mighty cataract of books I had been riding for years was beginning to feel insufficient. Nearly everything but what I was reading by Helen Garner, which was, if we want to think about books in those terms, “of use.” I underlined that particular paragraph because it articulated, in crystal-cut prose, exactly the unanswered questions I needed to hear in that moment.

I had read Monkey Grip before, but it wasn’t really until that year when I was twenty-two, when I was assigned The Children’s Bach in an Australian Literature Honours class at the University of Sydney, that my love affair with Garner’s work really began. The experience of reading The Children’s Bach was like suddenly realizing I’d been living with blurred vision after being handed a first pair of glasses. Had any book ever felt so clear? Early on in the novel, one of Garner’s many Philip’s tells his daughter Poppy a bedtime story about the Paradise Café, a place where people dance in the daytime. But when Poppy falls asleep, Philip continues: “It is not the kind of place outside which you would like to see your daughter sitting under the Cinzano umbrellas,” he says. “There is spilt liquid on the floor, dope is bought and sold, and girls fall over shrieking and have to be dragged outside with their friends.” As Philip leaves the room, he turns and tells his daughter in a whisper, “And men fuck girls without loving them. Girls cry in the lavatories. Work, Poppy. Use your brains.” Garner deliberately sets this, the most impactful sentence of the story, on its own across a line break. In my memory it was this, the parable of the Paradise Café, which shook me up. It caused me to physically gasp. I went home and I reread Monkey Grip. I had first bought it from Ariel Books in Paddington the afternoon I finished my Year 12 Biology exam, and I was told by the bookseller to “get ready.” Now, I got it, now I understood why the woman at Ariel Books had said, “get ready.” I hadn’t read anything quite like Monkey Grip before, something so episodic, its structure so much more like a diary or a notebook than the plotted, waveform structure of the novels I had so far been exposed to. Then I fell over the cliff. I read Postcards from Surfers, Cosmo Cosmolino, The First Stone, Honour and Other People’s Children, Joe Cinque’s Consolation, watched Two Friends and The Last Days of Chez Nous, studied the essays collected in True Stories, and the collection I was reading on Glebe Point Road at the beginning of this story, The Feel of Steel. This frenzy of reading when I was twenty-two, drunk on Helen Garner’s body of work, formed one of the most uniquely important reading experiences of my adult life.

Part of this was precisely because of the quality of my life at twenty-two. “Experience” had finally hit me, and I was desperate to find books which would help me understand what was happening. For months, I felt that what I was feeling and living through was entirely unwritten, or that if it was, it was an experience always being explained away by a retrospective voice, forcing the messiness and aliveness of experience into a narrative shape that eschewed the reality of what it was like to be alive in the chaos and messiness with no end in sight. I searched for books to help me understand, because that is what I had learned to do since childhood. It was in Helen Garner’s books that I found literature which represented some part of what was going on in my heart and my head, and elevated it to artistry, not just in its prose, but in its form. As I read, I began to see all of her work weaving together, the same inquiring voice emerge in the fiction, move into the wilder territory of non-fiction, and settle into a no-man’s land between the two that I had, until that point, not properly encountered before. The experience I was having with her work that year was blissfully uncritical, and it was crucial to turning me from a clever and competent Honours student into a writer.

In ‘Woman in a Green Mantle’ I encountered Garner articulating something key about her work, and key to what I found so liberating about it. She revisits the idea, long percolating in literary discussions that hadn’t reached me as an English undergraduate, that the novel is dead. She wrote, “Now, there exists a developed awareness of something honourable to offer in its [meaning the novel’s] place – I mean the dangerous and exciting breakdown of the old boundaries between fiction and non-fiction, and the ethical and technical problems that are exploding out of the resulting gap.”

This breakdown of the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction – that such a thing was even allowed – was utterly revolutionary to me that year, when I was twenty-two. But it would become the animating principle behind my own journey to becoming a writer, and what’s kept me coming back to Garner’s work ever since.

Where that all began, of course, was Monkey Grip. When Monkey Grip was published, the crime writer Peter Corris wrote the following in his review: “Helen Garner has published her private journal rather than written a novel,” he said. “The “I” of the book, Nora, is indisputably the author herself and the other characters are identifiable members of the Digger…Pram Factory set in Melbourne.” Corris wrote this as an accusation, as though he felt he had been duped or betrayed by the book. He wasn’t altogether wrong, in substance, because Monkey Grip was based on Garner’s autobiographical experience, and arose from a practice of note-taking and diary keeping which was inherently writerly. Bernadette Brennan, Garner’s biographer, (and who incidentally taught me during that providential year when I was twenty-two), notes that “Reading Monkey Grip as poorly disguised reality not only dismisses the creative process of shaping the story, it also ignores how and why the diarized basis for this novel contributes to its meaning.” For somebody like me, this was precisely what gave Monkey Grip its power. The diary is intimate, episodic, with an address that faces inwards, disregarding an assumed audience. The form lends itself to a discontinuous narrative, in which the story progresses through snatches, fragments, moving the reader through the novel’s world as though they were following life lived as it was, rather than circumscribed and shaped to the dictates of a preordained plot. It’s in the diary that the first-person voice I was so taken with in Garner’s work was to be found.

There was another piece included in The Feel of Steel called ‘Tower Diary’ which I read in that courtyard off Glebe Point Road, and experienced as a minor revelation. It was here that I first encountered Garner’s shaped and published diaries, or at the very least the first pieces that declared themselves as such. The diaries present as discrete entries, sometimes a full page and sometimes only one or two sentences, separated by white space and a triple asterisk. ‘Tower Diary’ is a depiction of the time immediately after the collapse of Garner’s third marriage, full of the materiality of the high-up apartment with its famous view, the particular loneliness of Sydney, shards of heartbreak emerging in unlikely places such as the Bondi Junction Davis Jones furniture department. The total combines to portray the real-time experience of a break-up’s devastation, in a way which was entirely new to me, and, as a young writer, formally electrifying. This narrative technique has been honed and refined over the course of Garner’s career – prose delivered in short, sharp blocks, with little explanation or context, the connective tissue done away with.

And to anybody who questioned the form, or treated ambiguously autobiographical prose as some kind of alarming anomaly previously unknown to Anglophone literature, Garner had something to say. “Why the sneer in ‘All she’s done is publish her diaries?’,” Garner asks in her essay ‘I’. “It’s as if this were cheating. As if it were lazy. As if there were no work involved in keeping a diary in the first place: no thinking, no discipline, no creative energy, no focusing or directing of creative energy; no intelligent or artful ordering of material; no choosing of material, for God’s sake; no shaping of narrative…It’s as if a diary wrote itself, as if it poured out in a sludgy, involuntary, self-indulgent stream—and also, even more annoyingly, as if the writer of a diary were so entirely narcissistic, and in some absurd and untenable fashion believed herself to be so entirely unique, so hermetically enclosed in a bubble of self, that a rigorous account of her own experience could have no possible relevance to, or usefulness for, or offer any pleasure to, any other living person on the planet.” The frustration and indignation of this excerpt from “I” felt, when I first read it, and when I read it now, like I was being given permission.

In 2019, Australians were given the first volume of Garner’s published diaries, The Yellow Notebook. Followed by another two volumes, and now collected into a single volume in the UK and US, these diaries are, I believe, the apotheosis of Helen Garner’s work, and the key to understanding everything else she has published. They are the key to her body of work, but a key that will only be of use to you once you’ve already read everything else she’s published.

In a 2019 conversation with Michael Williams at Sydney’s City Recital Hall, Garner said that it had been her publishers, Text, who suggested she compile a volume of her diaries. She went home and examined the remaining volumes (Garner infamously burned her early diaries in the late 1970s). Garner started transcribing the bits that she felt she could put on the page “without wanting to die of shame.” Importantly, what she was looking for was a common thread. She said, “I was taking out everything that didn’t feel like muscle.” When first reading the diaries, I assumed Garner must have revised her prose. I was wrong. She told Williams that she didn’t need to polish the prose, because the prose was measured when it was originally written. “The point,” she told Williams, “is to articulate coherently something about what I’m going through, or what I’ve experienced that day, or something that’s scared me or angered me or moved me…It wasn’t sloppily written, it was about things that were being sloppily felt.”

While the diaries may not have been re-written, the entries are carefully edited, selected and arranged. The “muscle” is evident everywhere. One of the main arcs of the first volume of diaries, The Yellow Notebook, is the slow disintegration of Garner’s second marriage. Much of the emotional resonance comes from Garner’s decision to portray the years-long frustrations her husband had with her decision to learn the piano. The petty irritations and grand fights that stem from Garner’s poor piano playing truthfully sketch the gradual wearing-away of affection, like sandpaper on soft wood. In 1984 she writes, “this is what will happen to me: He will leave me and go off with someone younger.” Which is, in fact, what happens. When we learn definitively of the marriage’s end, it’s through short, sharp fragments, of conversation or observation, reported without commentary: “M’s father, F and me walking in the cemetery with the dog,” she writes. “Now I have two ex-husbands.”

What persists across all of Garner’s writing is the ‘I’, a meticulously constructed portrait of a self, sometimes, but not always, named Helen. And to follow on from Bernadette Brennan “the ‘I’ in her journalism and nonfiction is, as Janet Malcolm has argued about her own work, ‘almost pure invention,’ a functionary connected tenuously to the actual writer.” Part of why I loved the diaries is that in the diaries the character of ‘Helen’ emerges in full force, fictional and non-fictional all at once.

The last time Garner published a book described as a ‘novel’ was 2008’s The Spare Room. At the time, Garner told the critic Caroline Burns: “It is morally a novel, even though it’s very closely based on my real experience of those three terrible weeks in my life. By calling it a novel I’m saying: this is not a memoir, this is not non-fiction, this is a novel and there will be things in here that are invented, that didn’t really happen, and I’m going to take…every sort of liberty I need to take in order to turn it into the sort of book I want it to be.” About a decade ago, I was re-reading The Spare Room. I had moved to New York when I was twenty-three, and I had, over successive trips home, brought back with me every copy of Garner’s books in my suitcase. One evening, during a party held at the offices of The Paris Review, I got into a fight with another Australian about how best to describe and characterize The Spare Room. The fight exploded with such animosity that the other Australian and I have not spoken to one another since. Ten years and counting.

The fight, for all its silliness, represented something particular to me in that period of time. Part of my argument that night had to do with Garner’s first person, an argument that it was the same first-person as existed in the rest of her work, that you couldn’t divide the fictional and non-fictional ‘I’ from each other. That the in-betweenness of the first person was, in fact, where the meaning was to be found. I can no longer remember what the other Australian’s position was.

It was around the time of this fight that I was in the early stages of writing my first book. And when I looked to other writers who gave me permission, whose work I annotated and reread and studied, they had in common an in-betweenness of the first person: Marguerite Duras, Lydia Davis, W.G. Sebald, Annie Ernaux, Derek Jarman, and Helen Garner. These were writers who produced work which was absolutely dictated by a first-person voice. The first person created structural possibilities that excited me, but it also collapsed boundaries between genres. It felt to me both the most exciting and the most truthful way of writing.

When I began writing what would become my first novel, The Inland Sea, I turned to the notebooks and diaries I have been keeping since I was eighteen. That novel, and my second, Elegy, Southwest, have at their foundation the diary form, the messy everydayness of what I noted down. They are, in large part, built from real experience. This was intuitive, but it’s a formal conceit that makes perfect sense when you look at who I was studying and learning from. There was something about that quality of the first person, the relationship it had to intimacy and truth and consolation, and the formal and structural possibilities it opened up for me, which made it the most natural mode to write in. It was clear to me that my books were novels – works of fiction – simply because I made things up. I used real life, the foundation of the diary, and came out the other end with a work of invention. Experience had been pulverized and made into an aesthetic medium. But that does not mean that I too haven’t encountered frustration from readers, or been accused, in so many words, of having published my journal instead of writing a novel.

When you write about yourself, when you find yourself awake at 4 in the morning wracked with doubt, the fear, sometimes, is that the ‘self’ is somehow not enough. Not enough because how can all the world be conveyed, explored, rendered meaningful, through one measly ‘I’. When I feel this way, I go back to basics. Why do I write? Why not paint, or dance, or play the cello instead? Because literature can do one thing that no other art form can do: It can let you experience what it is like to be inside the consciousness of another human being. I don’t think telling stories can fix any of the political or social problems the world is beset by, but nor do I think that’s its purpose. I do, however, believe that a first-person response to, for instance, climate change, structural inequality, political calamity, and the making of history, may be a profoundly meaningful, and truthful, representation of what it is like to be alive in the world right now. And that it might make being alive more bearable.

The structural possibilities of writing about the self are what excited me most about Helen Garner’s work during that epic of reading when I was twenty-two, and her work was a touchstone for what I wanted my own to be before I ever encountered anyone else working in the same in-between space. This is the space, to quote Garner one last time, of “the dangerous and exciting breakdown of the old boundaries between fiction and non-fiction.” It is that space that Garner has been writing into her whole career, the model I chose to take as my own all those years ago, and it is for that reason that the diaries might be her greatest achievement.

Loved your paper and it was great to get to meet you in Perth, Madeleine! I'm still processing how surreal it was to have Helen in the room, and just chat with her lightly over lunch, etc.

Love this introduction to Helen Garner, a writer I have only started to hear about here in Ireland through engaging in a really good Australian book blog. As a new reader of her work where would you recommend me to begin with regarding her novels? And this article has also illuminated the narrative voice process for me in Elegy, Southwest. A book I loved.