Baby Pictures

A few months ago, Westerly Magazine approached me about writing something for a special edition reflecting on archives. What I came up with is one of the things I’m most pleased and proud of having written this year, and so I wanted to share the piece with you here (the whole edition is available to download as a PDF here, but for those who aren’t in Australia, the print edition is going to be tricky to track down.) Great magazine, loved working with them.

I’ve spent most of the last few months writing into and around pregnancy - something I thought I’d do a lot more of in this space, but unfortunately life has gotten in the way. A short story that evolved from my being stung by a “mauve stinger” jellyfish when I was 7 weeks pregnant came out with Broadcast in September (here, for the curious), and there’ll be another essay out next month. It’s kind of strange (and feels frankly a little dangerous) to intellectually/creatively dwell so much in pregnancy in public, before birth, but it also feels incredibly fruitful and weirdly unexplored. Honestly, it’s hard to think about anything else. As I write this I can see my stomach rippling and rising where I am being kicked by tiny feet I have grown inside me. It’s wild how the most prosaic thing in the world - reproduction - can feel so uncanny and alien and entirely unspoken. I guess my point is, I’ve been trying to speak about it, before I come out on the other side.

Baby Pictures

(Published in Westerly Magazine: Archive Reflections, December 2025)

Two years ago, when I was visiting my mother back in Sydney, she suggested we go through old photographs. She retrieved several albums and boxes from the wardrobe in her bedroom, and brought them out to the veranda after dinner. The boxes and albums were chaotic and lacking any kind of chronology, full of the wardrobe’s mustiness. My mother refilled our wine glasses, began to lay out the photographs; I opened a notebook, and I took notes. That one, there, she was illegitimate. That man disgraced himself somehow at Gallipoli. A dark-haired woman in severe Edwardian lace was Mary, pronounced Mahr-ee. There was my grandfather as a young man, standing next to somebody called Billy Pew, who died of melanoma: ‘The first time Mum really saw Dad cry was when Billy Pew died,’ my mother remembered.

The whole evening felt like it was weighted with ceremony, with the official passing down of knowledge—after all, that was why I was making notes. If my mother was the knowledge-keeper of her generation, the daughter who had inherited the photographs, then I was to be the knowledge-keeper of mine. Who else was to remember that my grandfather wept over the death of Billy Pew, or that a woman named Mary pronounced it Mahr-ee?

As my mother flicked through the loose photographs in the boxes, I saw a blur of black and white faces which, for the most part, were completely unknown. Even though I understood that the people in the photographs were my relatives, I didn’t feel like they bore any actual relation to me. Outside of my mother’s stories, and the context she was lending the faces, they could have been strangers: antiquated haircuts and outfits and stony stares, in anyone else’s family photo album.

The photographs of my own grandparents, my own mother, myself—those were a different matter. Those people mattered to me, and I asked my mother if I could take some of the photos home to Berlin when I left. I came away with a Ziploc bag full of old photographs, and took copies with my phone of the prints that were too rare and precious for me to have.

For the last two years, those physical photographs have sat in a drawer of my desk, unexamined. That changed recently. A few months ago, I fell pregnant. At ten weeks, I went into the doctor’s office for the second ultrasound. I had seen on the internet already the illustrations of what a ten-week-old foetus looks like, more alien or sea creature than humanoid. At ten weeks it had only recently lost its tail, ears were just beginning to form. On the screen I could see two white lobes, tiny, one for a future-body, and one for a future-head. I was handed the print-out photograph of the sonogram, and took it home, stuck it on the fridge between the pharmacy’s pollen count calendar and a friend’s illustration of Walter Benjamin in a Where’s Wally? hat. Now I had a photograph, a physical thing I could hold, of my future-human.

Four weeks later, I had another ultrasound, this one with high-tech equipment in a doctor’s office on Kurfürstendamm, one of Berlin’s ritziest and most storied thoroughfares. Suddenly the foetus looked indisputably human. It had feet and hands, and a sex. Her nose was one of the first things I noticed on the screen—reminding me even in hazy black and white shadow of my grandmother’s nose. I had, that day on Kurfürstendamm, the distinct sense that time was bending. As I looked at the images of the baby on the screen, two things occurred to me: one day that tiny foetus in black and white would become an old woman; and that I was carrying the future inside me. In my body the eggs in my baby’s ovaries were forming, potential grandchildren. And part of me too, I suddenly realised, was formed in my own grandmother’s womb in 1958 when she was pregnant with my mother. The lineage of generations suddenly felt of phenomenal significance. I found myself, that day after the ultrasound, taking the old photographs out and splaying them across the dining table. I picked out those showing my grandmother, my mother, and myself, all as children. As though in studying three generations of faces I could pick out the first hint of the face my future child would carry.

When I was young, I would beg my grandmother for bedtime stories. My favourites were all about when she was a little girl. She grew up in the Blue Mountains without much money. Her mother died when she was eleven, after which her father pulled her out of school so that she could take care of her four-year-old epileptic brother, meaning my grandmother, with her beautiful penmanship and bookshelf of Australian classics, had not been educated beyond Grade Six. The stories I loved contained the grim elements of poverty, but they were also full of romance and adventure: her hair catching alight from the candle she used to reach the backyard toilet on a winter’s night, chasing down the postman for a cheque one morning so that she might be allowed to go to the Saturday matinee, getting so sunburned that her mother put her to sleep in the linen chest on the only sheets which didn’t aggravate the blisters. I have vivid images of my grandmother’s childhood, images that came from stories. What I don’t have are actual images.

The only picture I have of my grandmother as a child I first saw in those boxes and albums at my mother’s house. Just the one. She’s maybe four, and she’s been sat with one of her brothers—I’ve no idea which—on a cane chair at the edge of a veranda. The bow on her dress looks slightly threadbare, as do the cuffs. My grandmother had naturally curly hair, as do my mother and I. But I knew from her stories that as a child she was forced to sleep with her hair wound in rags to rid it of the ‘unruly’ natural curls, so that in the morning it could be let down in the defined, controlled ringlets popular in the 1930s. Her hair in the photograph falls in those tight ringlets, no trace of its real curl, and no trace of its colour—red—for which she was called ‘carrot’ by boys at school. She’s smiling in the way children smile when they’ve just been asked to say a word like ‘cheese’. Her fingernails are dirty. She holds in her hands a white bird. I hope it’s a toy. Either that or it’s dead. She’s squeezing it quite hard.

There’s only one picture of my grandmother as a child for good reason—it was more expensive to take photographs in the 1920s and 30s, and my grandmother’s family were poor. There wasn’t a camera that lived in the house, somebody brought one in. Photographs were precious. You got dressed up for them and posed, whether in a studio or, in this case, on the edge of a veranda. ‘Photography is an elegiac art,’ wrote Susan Sontag, a sentiment that, it seems to me, applies even more to family snapshots than to art or documentary photography. It restores to life that which is gone, it works always in reference to loss, or an anticipated loss. In pregnancy I have found myself crying, missing my grandmother, something I do not recall happening since her death in 2008. Looking at photographs of my grandmother—dead for nearly two decades—as a child feels vertiginous. There is a finite amount I will ever know about my grandmother’s childhood, and when I look at the picture, I feel immensely sad. I wouldn’t know it was her unless I had been told. The child grew up, got married, had children, grew old, and died. The child in the photograph will forever be squeezing that bird.

By the time my own mother was born, my grandparents owned a camera, and film was cheaper to buy regularly. It made a difference that my grandfather had smashed himself into a brick wall on a motorbike at seventeen, rendering him deaf in one ear and ineligible for war service. While his friends were conscripted and sent off in slouch hats to fight the Axis powers, my grandfather stayed home, won a scholarship to university, and became an engineer. Suddenly middle class, by the time my mother was born they had the means to photograph her.

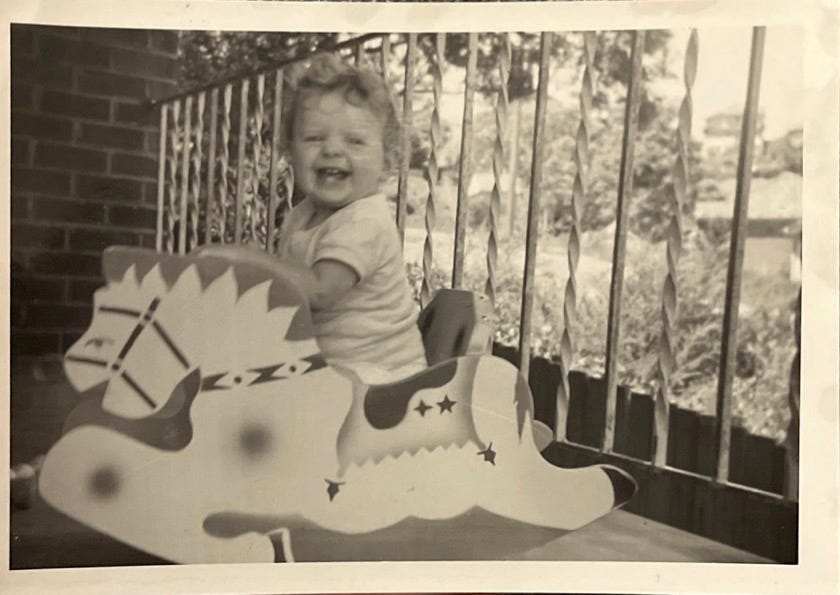

Of my mother as a baby, I have many photographs. In them, you can begin to see life. In the early stages, the photographs are small format black and white (cheaper to buy). She’s a tiny thing in bright white socks and christening dress being held up by my grandmother. She’s being held upright by my suddenly soft-jowled grandfather next to a thermos on a picnic table, smiling in thick woollens and a bonnet. She’s being fed by bottle on the edge of a paddock while my grandmother squints into the sun. After she was six months’ old, my grandparents must have bought a bigger camera, the dimensions grow larger, although only very rarely did they take pictures on colour film (always a special occasion, always posed). In black and white, my mother is grinning in the bath next to her baby brother, she’s cackling with laughter on a rocking horse, she’s running naked around the Lane Cove backyard in the path of the sprinkler, and a moment later she’s stopped, stark naked and dripping and deep in thought, holding a half-eaten apple in her hands. In these photographs of my mother, you get something more like a depiction of childhood in motion. She moves, she runs, she doesn’t always know she’s being photographed. She isn’t always posed. These photographs are most precious to me, and yet they were not the photographs that my grandmother kept in the official photo album dedicated to my mother’s childhood. These were extras, deemed somehow not good enough, left to float loose in a musty box.

Family photo albums are the most mundane of archives, but they’re ones which allow a family, or an individual to narrativise their lives. There are always, inevitably, exclusions. The choice of what to keep in, and what not to, amounts to a kind of proposal: this is life as it was lived according to the keeper of the archive. The blurry photograph of my mother-as-toddler, swinging back and forth on the rocking horse, or naked and wet and eating an apple; those pictures didn’t fit into the narrative of the album. These unposed, blurry photographs of my child-mother might, were it not for that night two years ago in Sydney, have been lost. What troubles me more is thinking about what other images probably have been.

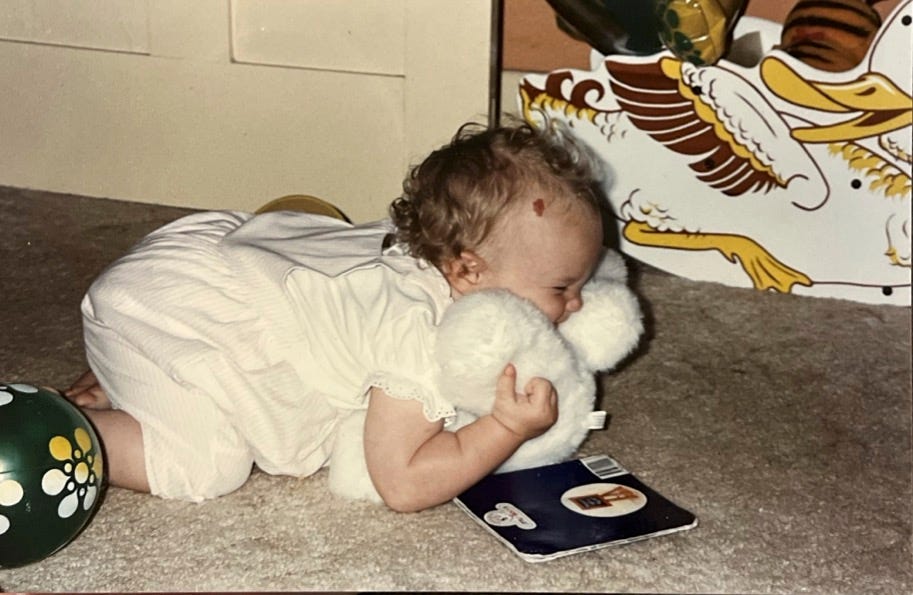

A little over three decades later, it was my turn. We had more than one camera, and colour film was cheap, was plentiful. Every trip to the supermarket could be accompanied by a trip to the photo shop, and the receipt of a paper envelope of uniform, shiny, neatly-stacked photographs, alongside the negatives. I was photographed constantly. The sheer volume of film, the sheer accessibility of the camera, meant I could be captured in all stages of activity—bouncing on my mother’s lap, upending a bowl of rice pudding on my head, systematically removing my mother’s creams from the bathroom drawers wearing a blue onesie. There is a strobe-light quality to some of the photographs. Here I am feeding a toy bottle to a white stuffed bear. Here I am holding the bear out in front of me in both hands, beaming at it. Here I am on my hands and knees, face buried in the bear which now lies on the floor as I smother it in kisses.

Like most people my age, I have scanned or photographed with my phone childhood photographs like these, and I have uploaded them to Instagram or Twitter. I’ve posted them, I suppose, to illustrate a kind of point, to provide nostalgic evidence of my own childhood in the halcyon 1990s. A lot of the pictures my mother let me take in the Ziploc bag have lived digitally in my phone for much longer than that, and I’ve looked at the poor copies more often than the physical Kodak prints.

But helpfully, on the back of most of the photographs I was allowed to take, in my grandmother’s beautiful penmanship, my age is marked: Madeleine at five months, two months, ten months. Occasionally it will say who I’m with, as in ‘Madeleine at 3½ months with Nana.’ When I have examined the photographs since I’ve been pregnant, it is with these numbers in mind. What does a baby look like at three and a half months? Does she have hair? (No) Can she smile? (Yes) And, more importantly, will my own baby look a little like that baby in the photograph? In one picture, my grandmother holds me: there is her thin, gold wristwatch, her rheumy, pink-lined eyes, her freckled hands, her red, curly hair. She looks nothing in 1990 like the little girl squeezing the bird on the veranda in 1930. And nor do I look anything anymore like the baby in her arms. The photograph of the two of us doesn’t take me out of time. What it does prove is that we once existed, exactly like that, together.

While I was writing this piece, I began to experience a kind of anxiety I hadn’t yet felt during the early months of my pregnancy. When I was about eighteen weeks pregnant, I felt a fluttery, tumbling sensation in the lower right-hand side of my belly, which felt very much like the kinds of flutters and tumbles I had been told were the first signs of foetal movement. I felt the flutters and tumbles when my husband and I were walking along the river by our apartment, when he spoke into my stomach, and when we played a Donna Summer record very loud. And then I didn’t feel them again. As I edged into twenty weeks and then on into twenty-three, I began to worry. There was nothing else wrong with me, no bleeding or pain or fever, in all other respects the pregnancy seemed normal. The midwife didn’t think there was anything to worry about, and said, ‘you might have thought you felt the baby move…’

The thing was, I had also seen her move. I had received a new sonogram photograph of the foetus during that fluttery, tumbling week, at the monthly ultrasound, I had seen her tiny feet curled up beneath her and rubbing together like her father as he falls asleep. But after a week, the reassurance of the image no longer held the same power. I Googled foetal heartbeat monitors and whether or not one could buy an at-home ultrasound kit in Germany, knowing to do so would be to invite a level of madness into our lives that couldn’t really be withstood. I searched for the kind of extortionate businesses an American friend had told me they’d visited in Texas, where you can pay for a medically unnecessary ultrasound in order to get a series of good photographs for your friends, or a recording of the foetal heartbeat placed inside a teddy bear. I thought these clinics were grotesque, but if there’d been one available in Berlin, I would have booked an appointment in a heartbeat.

One morning, talking to my mother back in Sydney about some of these anxieties, she said, ‘your problem is that you’ve seen too much.’ When she was pregnant with me, my mother said, she only had the one ultrasound, and it wasn’t very clear or exact. At all other times she just trusted that I was safe inside her stomach, doing okay. It was a whole different ballpark for me—I had been fed images from the opening weeks of the pregnancy, and got them on a monthly basis, sometimes even more frequently than that. I had so many sonogram prints stuck to the fridge between the pollen calendar and Walter Benjamin as Wally. I was used to getting regular updates from the transducer, pinned my sense of comfort and reassurance to the production of those black and white images. It’s the photographs that were the problem, my mother thought: too much knowledge a dangerous thing.

During this period, I created a new ‘album’ on my phone titled ‘Baby’. In it are included photos of the foetus when she was the tiniest smudge in my belly, through pictures of her heart and brain and umbilical cord at fourteen weeks gestation, and recent pictures of her now, in proportion, accumulating centimetres and grams. I have pictures of her jumping and rubbing her nose and touching her own feet. There are over thirty images in the album, all of a child that has not yet been born, and most of which don’t exist as physical images stuck to the fridge—the majority have been delivered to us via QR code and downloaded in bulk to my phone. The album on my phone is an archive of the future—it delivers me images of a life before life has yet begun. It is a kind of anti-elegy. It doesn’t restore to life that which is gone, instead the loss it anticipates is, in fact, life.

I find the existence of these images uncanny, unsettling—a part of me thinks that they should not be. But I look at them all the time. I have looked at them while writing this piece, for reassurance, for some acknowledgment that she’s there. When she is an adult, there will exist an archive of images, all digitised, documenting the development of her image from the eighth week of gestation. She will be born one hundred years after my grandmother, of whose childhood I have just a single image.

I’ve put photographs of myself as a baby on the internet, but I have posted none of the pictures in the ‘Baby’ album to social media. Nor will we once she’s born. If a photograph one hundred years ago was a precious thing, rare, there seems to me something quite unnerving and almost obscene about the ubiquity of photography now, its commodification, the revolutionised status of the image now that all photographs can exist in an infinite archive, innumerable, and in perpetuity. Displaying pictures of your children is different now, different to my grandmother’s single album of my mother, and my mother’s many albums of me. I have seen too many children, of friends and in public, put their hands up in front of their faces and cry out ‘No photos!’ as a parent holds up a phone, as though every child now were a mid-century film star hounded by paparazzi. To see them makes me wonder whether the revolt against the photograph is gestating amidst the very youngest members of our society.

While writing this piece, I went for the second round of prenatal diagnostic screening. This time we were going to check for any anomalies in the baby’s anatomy. I lay back on the medical table with my husband sitting in a chair beside me, the screen enormous and hovering above us. There she was. She was bent-double, her feet paddling over her head, and she was hiding, the doctor said, behind my stomach. It was difficult for him to get a good image.

One of the big highlights of the experience is the moment when the doctor pushes a button and you enter a 3D rendering of the womb, all orange and beige. Friends had shown us their own versions of these eerie images: scrunched-up faces, thumb-sucking, taking a drink of amniotic fluid. Only, when the doctor pressed the button, we couldn’t see her. Or rather, what we could see were two little knees, and two little forearms, held straight up over her face and obscuring it. I would prefer not to, said my husband. Out on Kurfürstendamm among the designer storefronts and linden trees, this seemed, we said, like a good sign. An early refusal of the camera, a refusal to let us ‘know’ any more than we need to know for now.

Works Cited

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrer, Strous and Giroux, 1977.

holding this close <3

"The photograph of the two of us doesn’t take me out of time. What it does prove is that we once existed, exactly like that, together."

What a lovely article and thank you for sharing your very personal experience Madeleine. I loved your thoughts on family photos and preserving the past for the future generations. Best of wishes 🤞